R.K. Narayan (10 October 1906 – 13 May 2001)

Rereading: RK Narayan

A visit to the city that inspired RK Narayan's fictional south Indian town, Malgudi, on the 10th anniversary of his death

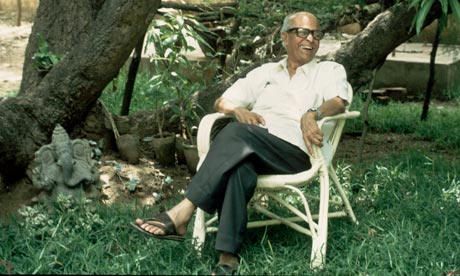

The author RK Narayan. Photograph: Simon Winchester

An old-fashioned pictorial map shows the small south Indian town of Malgudi as it would have looked some time before independence. There is the Albert Mission College, the Ishwara temple, the Welcome restaurant, a cinema called the Palace Talkies. Walking west along Market Road you would pass Dr Pal's Tourist Bureau, and the local offices of the Madras Daily Messenger, and then the statue of a former British governor, Sir Frederick Lawley, after whom the Lawley Extension housing-project is named. To the north the town is bounded by the Sarayu river, near which can be found the Untouchables' village, where Gandhi stayed on a visit to Malgudi in 1937, and the Sunrise Picture Studios, where Mr Sampath the printer made an ill-fated venture into the film industry. Beyond the river rise the Mempi Hills, with tigers and bamboo forests and hidden temple-caves.

The map is, of course, a cartographic fiction, for Malgudi exists only in the pages of a book – or more precisely, in the pages of 22 books (14 novels and eight short-story collections) written over a period of nearly 60 years by the great Tamil novelist RK Narayan, who died 10 years ago this week. The style is spare and droll – impeccable English with what used to be called an Indian "twang" – and the eye sharp and unsentimental, and the little provincial world of Malgudi is so convincing that you are soon drawn in. One of the first to succumb to its charms was Graham Greene, who in 1935 was instrumental in getting Narayan's debut novel, Swami and Friends, published in England. It was also his idea that the author – Rasipuram Krishnaswami Narayanswami – should be styled more succinctly on his title-pages. "Narayan wakes in me a spring of gratitude," Greene later wrote. "Without him I could never have known what it is like to be Indian."

The Malgudi stories are a meandering south Indian soap opera, full of small-town intrigues and aspirations, and they were successfully translated to Indian television in weekly episodes in the 1980s. As with most soap operas, it is easy to get hooked – easy, indeed, to become a bit of a Malgudi nerd, as witness Dr James Fennelly of New York's Adelphi University, who compiled the above-mentioned map to illustrate a learned paper ("The City of Malgudi as an Expression of the Ordered Hindu Cosmos") that he delivered to the American Academy of Religion in 1978. The map is both a tribute to the rich verisimilitude of Malgudi, and a faintly Malgudian enterprise in itself. It clearly tickled the author, and was published at his request in the front of his 1981 collection, Malgudi Days.

That "ordered cosmos" that Fennelly discerned has been a cause for criticism. Narayan is a bit unfashionable these days – his laconic voice seems out of touch with the firecracker talents and political activism of new Indian fiction. VS Naipaul has spoken of the "stasis" in his work; the world he depicts is "a fable", though Naipaul also notes perceptively that Narayan's interest lies not in the surface currents of social change but in "the lesser life that goes on below: small men, small schemes, big talk, limited means" – an excellent synopsis of the Malgudian ethos.

Things do change in Malgudi – in the later novels (the last was published in 1990) there are "scooter-riding boys" and auto-rickshaws in the streets, and hotels serving European food, and a hydro-electric project in the Mempi Hills – but the town remains trapped in a dusty miasma of daily preoccupations in which pre- and post-independence are only hazily distinguishable. Narayan is sometimes called the Indian Chekhov: a master of the inconsequential and its hidden depths. In Waiting for the Mahatma, the tide of Gandhian reform sweeps into town, in the person of Gandhi himself, but when the signwriter Sriram is hired to paint "Quit India!" slogans on the walls, he is mostly concerned with getting the tail of the Q as short as possible to save on paint. In The Vendor of Sweets, Jagan sorts the small coinage of the day's takings "with the flourish of a virtuoso running his fingers over a keyboard".

Malgudi cannot be visited, however much one would like to, but in this anniversary year I was glad to find myself in the atmospheric city of Mysore, a hundred miles south-west of Bengaluru (formerly Bangalore). It is a place of considerable charm, with a long tradition of princely independence, and at an altitude of 2,000 feet in the foothills of the Western Ghats it has a delightful climate. It was here that Narayan lived for most of his life, and here that he found much of the raw material for Malgudi.

Born into a large Brahmin family in Madras (now Chennai) in 1906, Narayan came to live in Mysore as a teenager in the 1920s, when his father was appointed headmaster of the Maharaja's Collegiate High School. In those days it was a place of "quiet demeanour", says Sunaad Raghuram, a prominent local journalist and a lifelong fan of Narayan (or "RKN", as he is often known here). It was "a royal city, full of stately buildings, but not really like a city – a little town". This suited Narayan, who was "a small towner at heart". Narayan himself characterised it as a city of talkers. The vital issues of the day "were settled on the promenades of Mysore", he wrote in his 1974 memoir, My Days. "If Socrates or Plato were alive, he would have felt at home in Sayyaji Rao Road and carried on his dialogues at the Station Square."

Mysore today is no longer the small sequestered city-state of the 1920s and 1930s. It has a population nearing 900,000, and all the problems of traffic and overcrowding endemic in Indian cities. But it still has that easy-going, chatty, intellectual energy of a university town with a strong sense of its own identity – though Plato would find Station Square a less congenial spot for philosophising, as it is now a parking area packed with scooters and motorcycles.

Raghuram did not know Narayan personally, but as a child in Mysore in the 1970s he often met a jovial character called Mr Chaluvaiengar, who was a friend of his aunt's. He was a noted amateur actor, putting on Shakespeare plays in the local language, Kannada, but by profession he was a printer. At his City Power Press, in a little house near the maharaja's palace, were printed the first Indian editions of Narayan's early novels. And suddenly one slips across into Malgudi, for Chaluvaiengar was undoubtedly the model for Mr Sampath, owner of the Truth Printing Works on Kabir Lane, and eponymous hero of Narayan's fifth novel – a jaunty and very persuasive man. "When he took a sheet from the press he handled it with such delicacy, carrying it on his palms, as if it were a newborn infant, saying 'See the finish?'", and his customer, though privately disappointed that the dummy copy of his idealistic new magazine looked like "the handbill of a wrestling tournament", was "half-hypnotised into agreeing with him".

After graduating in 1930 from the Maharaja's College – prototype of the Albert Mission College in Bachelor of Arts – Narayan decided to "throw [himself] full-time into this gamble of a writer's life". In his memoir, he recalls with affection his first typewriter – an "elephantine" Smith Premier 10, which had separate keys for upper and lower cases, and which he had to sell to a shopkeeper to pay an overdue bill for sweets and cigarettes. One of his first professional assignments was as the Mysore correspondent of a Madras newspaper, the Justice. All morning he "went out news-hunting" in the bazaar and the law courts and police stations, gathering everything from crime stories to gymkhana results. At 1pm he returned home, "bolted down a lunch", typed up his report, "and rushed it to the Chamarajapuram post office before the postal clearance at 2:20pm". He aimed to produce "ten inches of news" a day, at a rate of about 15 annas an inch, but "thanks to the news editor's talent for abridgement" his earnings were minimal.

Though he dismissed this work as "a little bit of pot-boiling", one can see that the news-hunting Mysore stringer is an important forerunner of the chronicler of Malgudi – an ambulant, inquisitive figure, "going hither and thither", his antennae tuned for stories. Narayan's daily walks through the city became the habit of a lifetime. His nephew, RS Krishnaswamy, has recorded some memories of these, estimating that a typical promenade would cover about seven miles. "After his ablutions, and chanting the 108 Gayathri mantras, he was ready for his daily walk at 10. Dressed in a white shirt and white panche [dhoti] and carrying his legendary kode [umbrella] he would slowly walk, never briskly, always talking to everybody on the road."

He was a frugal man – his lunch was rice and curds with a bit of pickle, the classic Brahmin dish – and physically slight. His childhood nickname, Kunjappa (Little Fellow), followed him through life. In later years he was described as looking like "a very intelligent bird". In photographs with his wife, the strikingly beautiful Rajam, he is shorter than her. Rajam died young, of typhoid, in 1939, an experience relived in his most sombre novel, The Dark Room. Narayan's name is well-known here, but is oddly lacking in official recognition. "He is an internationally recognised writer, and Mysore was his muse," says Raghuram, "but there is not a road named after him, not a circle [roundabout] named after him." (There is, admittedly, a Malgudi Coffee Shop in the upmarket Green Hotel just outside Mysore, but that seems more branding than commemoration.) In 2006 a petition was sent to the governor of Karnataka, proposing that the Chennai-Mysore train service be christened the Malgudi Express. This seems an eminently sensible idea, but the railways minister has other priorities, it seems, and the request remains pending.

There is at least one place in Mysore where you can put your finger on the elusive RKN – at his former home, up in the northern suburb of Yadavagiri. It was built to his own specifications in the late 1940s. The area, then rustic and isolated, is now a leafy street in a pleasantly breezy uphill location, but the house stands empty and rather forlorn, with a look of out-of-date modernity – two storeys, cream-coloured plaster, with a stoutly pillared verandah on the first floor. The idiosyncratic touch is a semi-circular extension at the south end of the house, like the apse of a church. On the upper floor of this, lit by eight windows with cross-staved metal grilles, he had his writing room. It had such a splendid view over the city – the Chamundi Hill temple, the turrets and domes of the palace, the trainline below the house – that he had to curtain the windows, "so that my eyes might fall on nothing more attractive than a grey drape, and thus I managed to write a thousand words a day".

A few hundred yards up the street stands the smart Hotel Paradise. The manager is Mr Jagadish, a courteous and slightly mournful man with a neat grey moustache. He knew Narayan in the 1980s, when he would sometimes dine at the hotel with his equally famous younger brother, the Times of India cartoonist, RK Laxman. I ask what he was like, but it is Laxman who stands out in his memory. Laxman was "very funny", and had opinions about everything, but Narayan was "more serious". He was a modest man, he didn't "blow his trumpet". Sometimes, says Mr Jagadish, he has guests who ask him: "Where is Malgudi?" He laughs and taps the side of his head. For a moment I think he is giving an answer to the question – that Malgudi was all inside one man's head – but what he means, of course, is that the question is daft. Narayan was asked it many times, and ducked it in a variety of ways. One of his more enigmatic answers was this – "Malgudi is where we all belong, and where we wish we lived."

The way with which R K Narayan makes us see through a 10 year old's eyes deserves appreciation. This is one of those books where you can relate to with.

ReplyDeleteThe characters are etched deep into our hearts. When Rajam bids adieu, you feel a lump in your throat. You never mind reading it again and again to get into the world of swami.

The best children's book I have ever read, and the only book which has made me laugh so much.

P.S- If you are a Tamilian, read the book for sure, you can enjoy it even more.