for those who love good prose... Suprose aims to encourage and support literature, authors, books and audiences of SA prose. Think of this as a watering hole where conversations begin and friendships develop.

What is Suprose?

Welcome to Suprose.

Why Su-prose? "Su" in Sanskrit is a prefix for "good". This is a place where we will discuss and analyze prose (with a South Asian Connection) - that which is good, awesome, excellent, and maybe rant about prose that could be better.

Whether you love prose, are a prose expert, or want to learn more about prose, or to put it simply want to have anything to do with prose, this blog is for you.

Why Su-prose? "Su" in Sanskrit is a prefix for "good". This is a place where we will discuss and analyze prose (with a South Asian Connection) - that which is good, awesome, excellent, and maybe rant about prose that could be better.

Whether you love prose, are a prose expert, or want to learn more about prose, or to put it simply want to have anything to do with prose, this blog is for you.

Read, interact, enjoy and share...

Search This Blog

Saturday, March 24, 2012

Monday, March 19, 2012

The Roundtable - Writers Block: Is It All In Your Head?

In this month's featured author Tête-à-Tête, Thrity Umrigar, (http://suprose.blogspot.com/

Suprose talked with three prolific authors about their thoughts on Writers Blocks. Do they/Should they exist? How should writers address it, to best overcome and surge ahead with their writing?

Uma Krishnaswami is the author of over a dozen books for young readers, from picture books through novels.

|

| Uma Krishnaswami |

But what I can and do understand and experience, is something I call "writer's emptiness." Sometimes I feel as if I have simply used up all my words. I have no more left. The good thing is that when this happens, I have learned to recognize the feeling. If my word bag is empty, I need to go fill it up all over again.

The way to do this is also simple. When I feel as if writing has drained me of language, I replenish it by reading. I read for a few days straight, and I try to pick up a wide variety of texts. Sometimes I deliberately read work that is really different from the current work in progress.

A few days of this, and when I return to writing, I always find that the energy gradually returns; the spring begins to bubble again. I should add that not only do I feel this emptying at least once with every major project I've ever undertaken, but that if it didn't, I'd worry. It's part of the process. If a story doesn't challenge me by using up everything I can throw into it, then it means I haven't worked hard enough, or gone deep enough.

I suppose what I'm saying is that you have to find the metaphor that moves story along for you, whatever that metaphor is. You can't be self-indulgent, but you must be self-aware. Of course it's all in your head, but so is fiction. In the end, our thoughts and intuitions are the only instruments we have. We have to work with them, not against them."

Uma Krishnaswami was born in India and now lives and writes in northwest New Mexico. Kirkus Reviews called her latest novel, The Grand Plan to Fix Everything "...as wonderfully convoluted and satisfyingly resolved as any movie plot could be." Uma is widely recognized for being a major voice in the sharing of international and multicultural viewpoints in children's literature. She is also on the faculty of the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA program in Writing for Children and Young Adults.

Author Mira Kamdar's essays and opinions appear frequently in The Caravan magazine, the New York Times' blog India Ink, and the Courrier International.

|

| Mira Kamdar |

"My fail-safe cure for writer’s block is a deadline. In fact, I am writing this now only because I’ve been given a deadline of tomorrow.

With a few exceptions, such as when editors ask me to turn around a short piece within days, or even hours, the deadline begins its life as a remote thing. I put it on my electronic calendar and forget about it: closer deadlines occupy my immediate attention. At some point, the deadline begins to haunt me. As time hurtles me toward it, I start thinking more and more about what I have to write. Since I write nonfiction, there is generally a certain amount of research I need to do before I am ready to write. I find myself, between other tasks, starting to notice anecdotes, news stories, conversation snippets that relate to my writing assignment. If I need to do substantive research or interviews, I schedule first visits to archives or libraries and send the first emails or make the first phone calls to people I want to interview. I collect my notes and any other material in a folder. As I review and add to these, I experience a series of “ah-ha” moments where obvious points reveal themselves. These points start to connect with each other. This process is largely driven by my subconscious which always is working much more consistently on the writing assignment than I am consciously working on it. As the deadline approaches, connections start multiplying furiously. At some point, a working title emerges that seems right.

Meanwhile, I often find myself finishing up all kinds of tasks that have nothing to do with the deadline but that I can get done easily and which give me the comfort of having completed useful things. These tasks can be as basic as cooking dinner or doing laundry or paying bills or readying tax returns. This temporarily soothes my growing discomfort with the unfulfilled deadline. As the deadline approaches, however, it begins to scream silently at all hours of the day and night no matter what else I am doing. At some point, as close to the deadline as I dare, it all becomes unbearable and I sit down to write.

I usually have a few rapid false starts with the opening sentence. Finally, I get one typed that satisfies me and that opens up a path to what must follow it. As I write, as I begin to give narrative form to what is still usually at most a list of essential points I want to make, the writing starts to take over. The real pleasure comes in those moments where the words seem to write themselves, surprising me by their flow and the way they articulate exactly what I didn’t know I wanted to say. The real pain is coming up against moments where I am at a loss for words, where I think I know what I want to say but can’t get it to come out right on the page. Sometimes, I have to just get up and go do something else and come back to it.

Then comes the rewriting. For me, rewriting can throw up a bigger block than writing. Often, I have to sacrifice the very passages I thought were the best when I wrote them. I usually have word limits, and I always have to cut a lot and think of more economical ways to say what I want to say. This can feel like infanticide.

My biggest writer’s block is one I have lived with for decades now. It’s hampered me for so long, I’m sure, because there is no external deadline, and I haven’t been able to impose one on myself. This is the block I have about writing fiction. I really want to write fiction. Several of my editors have told me, based on my nonfiction writing, that I should write fiction. Over the years, I have had many ideas for stories and I still harbor a couple of ideas for novels. Yet, I can’t get started. I am seized by panic and fear when I even think about starting. I cope by taking refuge in multiplying nonfiction deadlines. That way, I feel like I am accomplishing something while the thing I most want to accomplish remains undone. Nonfiction writing is the way I cope with my fiction-writing block. The more awful I feel about not writing fiction, the more furiously I write nonfiction. This strategy has worked for decades to defer the terrifying moment of sitting down to write what I really want to write, but I’m not sure it will work forever. What will happen if I ever break through that block, I cannot tell."

Mira Kamdar: Born to a Gujarati father raised in Burma and India and a Danish-American mother raised on a farm in Oregon, Mira Kamdar has navigated between different localities and identities her whole life. As a four-year-old, she asked her mother: “Which way am I half? Up and down? Or sideways?” She is still trying to find the answer to this question.

Her books, Motiba’s Tattoos: A Granddaughter’s Journey from America into her Indian Family’s Past (Public Affairs 2000; Plume 2001) and Planet India: The Turbulent Rise of the World’s Largest Democracy and the Future of our World (Scribner 2008), hav been translated and published in over a dozen foreign editions, including Hindi, Chinese, Arabic, Dutch, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and French. She lives in Paris, France.

Padma Viswanathan, writes fiction and is the award winning author of "The Toss Of A Lemon"

|

| Padma Vishwanathan |

"I said to myself this morning, as I circled, for a second day, around a difficult topic, “It’s not going to be good.” I meant my writing: there was no way that my first try at writing this very difficult new material into my existing novel draft was going to result in anything truly readable. Whatever I put down, I had to be prepared to wince when I first re-read it. At worst, it would be no more than a place marker. At best, it might contain a few phrases tonally accurate enough to keep through what I knew would be multiple, decimating revisions.

“Writer’s Block,” as far as I can tell, often comes from an artificial perfectionism, from the need to have something right the first time. I think this is almost always true for inexperienced writers. I admit that, in the case of experienced writers, it can signal something deeper. There could be psychological problems at work: they are endemic among writers, and not to be ignored, but there again: it’s still not “writer’s block,” exactly. It’s a sign pointing elsewhere.

Other times, it might be that the writer hasn’t yet penetrated the problem. It can be useful in that case to let the brain rest and work differently, instead of clenching fists and screaming at the page or screen. As Hanif Kureishi says here, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/19/opinion/sunday/the-art-of-distraction.html?scp=2&sq=hanif%20kureishi&st=cse, the best route to insight is not always the most obvious or direct one. As Don Draper advised an underling, once: “Think about it deeply. Then forget about it. It will jump up and hit you in the face.”

Sometimes I need to wait it out, take a nap, make a cup of tea. Do some weeding; read about people with worse problems than your own. It’s just writing. It can wait. It can wait years if you need it to, but usually you won’t.

Sometimes there is a real-life problem, something urgent and troubling that I need to deal with before I can return to imaginative work.

But when it’s a case of fearful self-criticism, as it so often is, I make myself remember that even if it’s bad, it’s good enough. All I needed was to force myself to splash on the first layer of paint. Then I’d be able start scraping, and blending, layering and texturing. But unless you pinch your nose and start—Write it! Write the stinker!—none of that can happen.

Thrity’s right: Denying the existence of Writer’s Block is a healthy, even a robust, epistemological stance. Writing works best when it is an act of discovery, while Writer’s Block implies some foregone conclusion about what must be written—a deadening impulse, one that denies the surprise knowledge that sometimes can only emerge in the act of writing itself.

And look: after reassuring myself that it was going to be awful, so that I could go ahead and write without expectations, I got the passage out and, when I read it over, I heard myself saying, it’s good. It’s good."

Padma Viswanathan is the author of some plays, some journalism and the novel The Toss of a Lemon. Her second novel will be published by Random House Canada in summer 2013. More information, if you want it, can be found at www.padmaviswanathan.com

What are your thoughts on Writers Blocks? Leave your comments below...

What are your thoughts on Writers Blocks? Leave your comments below...

Saturday, March 17, 2012

Jhumpa Lahiri On Sentences...

In an elegant essay in the New York Times titled "My Life's Sentences", Jhumpa Lahiri writes,

What is one of your favorite sentences? Let us know in the comments section below.

"I remember reading a sentence by Joyce, in the short story “Araby.” It appears toward the beginning. “The cold air stung us and we played till our bodies glowed.” I have never forgotten it. This seems to me as perfect as a sentence can be. It is measured, unguarded, direct and transcendent, all at once. It is full of movement, of imagery. It distills a precise mood. It radiates with meaning and yet its sensibility is discreet."Sentences are the beginning, the middle and the end of any written piece. About the beginning sentences, she writes:

"The first sentence of a book is a handshake, perhaps an embrace. Style and personality are irrelevant. They can be formal or casual. They can be tall or short or fat or thin. They can obey the rules or break them. But they need to contain a charge. A live current, which shocks and illuminates."Then as she works of the middle part of her story/novel, here is how it comes together:

My work accrues sentence by sentence. After an initial phase of sitting patiently, not so patiently, struggling to locate them, to pin them down, they begin arriving, fully formed in my brain. I tend to hear them as I am drifting off to sleep. They are spoken to me, I’m not sure by whom. By myself, I know, though the source feels independent, recondite, especially at the start. The light will be turned on, a sentence or two will be hastily scribbled on a scrap of paper, carried upstairs to the manuscript in the morning. I hear sentences as I’m staring out the window, or chopping vegetables, or waiting on a subway platform alone. They are pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, handed to me in no particular order, with no discernible logic. I only sense that they are part of the thing.

Over time, virtually each sentence I receive and record in this haphazard manner will be sorted, picked over, organized, changed. Most will be dispensed with. All the revision I do — and this process begins immediately, accompanying the gestation — occurs on a sentence level. It is by fussing with sentences that a character becomes clear to me, that a plot unfolds. To work on them so compulsively, perhaps prematurely, is to see the trees before the forest. And yet I am incapable of conceiving the forest any other way.And then as she nears the end of her work:

As a book or story nears completion, I grow acutely, obsessively conscious of each sentence in the text. They enter into the blood. They seem to replace it, for a while. When something is in proofs I sit in solitary confinement with them. Each is confronted, inspected, turned inside out. Each is sentenced, literally, to be part of the text, or not. Such close scrutiny can lead to blindness. At times — and these times terrify — they cease to make sense. When a book is finally out of my hands I feel bereft. It is the absence of all those sentences that had circulated through me for a period of my life. A complex root system, extracted.Sentences are also her tool to fight writers blocks, it sounds like,

"The urge to convert experience into a group of words that are in a grammatical relation to one another is the most basic, ongoing impulse of my life. It is a habit of antiphony: of call and response. Most days begin with sentences that are typed into a journal no one has ever seen. There is a freedom to this; freedom to write what I will not proceed to wrestle with. The entries are mostly quotidian, a warming up of the fingers and brain. On days when I am troubled, when I am grieved, when I am at a loss for words, the mechanics of formulating sentences, and of stockpiling them in a vault, is the only thing that centers me again."It is a lovely and inspiring piece. Read the full essay here.

What is one of your favorite sentences? Let us know in the comments section below.

Sunday, March 11, 2012

Win a copy of "The World We Found" by Thrity Umrigar

This month Suprose will be giving away 3 copies of Thrity Umrigar's The World We Found. The Suprose interview with Thrity Umrigar is here. Read reviews of the book -- from the Boston Globe and from the Washington Post.

Want to win one of 3 copies of The World We Found?

Here is what you need to do --

Three people will be randomly selected on Saturday March 31st to win a copy of the book. You will be contacted via email.

Want to win one of 3 copies of The World We Found?

Here is what you need to do --

- Click on this link

- Read the exclusive interview with Thrity Umrigar and

- Leave your name and email in the comments section by midnight EST on Friday March 30th.

Three people will be randomly selected on Saturday March 31st to win a copy of the book. You will be contacted via email.

Thursday, March 8, 2012

Austin Kleon on 10 Things Every Creator Should Remember But We Often Forget

Read the full article on brainpickings here

Tuesday, March 6, 2012

Friday, March 2, 2012

The Guardian's 10 of the best books set in Mumbai

A fabulous new list from The Guardian -- 10 of the best books set in Mumbai

Malcolm Burgess, publisher of the City-Pick series, selects his favourite stories and essays set in the city. He says, Mumbai's extraordinary colour, energy and humanity are captured in some of the most celebrated writing of the past three decades.

See the full Guardian piece here.

Photograph: Public domain/David Pearson/Rex Features

Photograph: Public domain/David Pearson/Rex Features

Photograph: Public domain/Abraham Nowitz

Photograph: Public domain/Abraham Nowitz

- Malcolm Burgess

- guardian.co.uk,

Salman Rushdie, The Moor's Last Sigh, 1995

The beautifully written but also very funny novel of a vanishing Mumbai.

"Once a year, my mother Aurora Zogoiby liked to dance higher than the gods. Once a year the gods came to Chowpatty Beach to bathe in the filthy sea: fat-bellied idols by the thousand, papier-mâché effigies of the elephant-headed deity Ganesha or Ganpati Bappa, swarming towards the water astride papier-mâché rats – for Indian rats, as we know, carry gods as well as plagues … There were, in addition, many Dancing Ganeshas, and it was these wiggle-hipped Ganpatis, love-handled and plump of gut, against whom Aurora competed, setting her profane gyrations against the jolly jiving of the much-replicated god."

• Chowpatty Beach

• Chowpatty Beach

Gregory David Roberts, Shantaram, 2003

The compelling autobiographical novel of an Australian criminal who escapes to a new life in Mumbai.

"The first thing I noticed about Bombay, on that first day, was the smell of the different air … it's the smell of gods, demons, empires and civilisations in resurrection and decay. It's the blue skin-smell of the sea, no matter where you are in the Island City, and the blood-metal smell of machines. It smells of the stir and sleep and waste of sixty million animals, more than half of them human and rats … It smells of ten thousand restaurants, five thousand temples, shrines, churches and mosques, and of a hundred bazaars devoted exclusively to perfumes, spices, incense and freshly cut flowers."

• Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport

• Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport

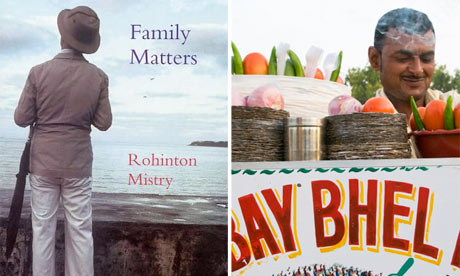

Rohinton Mistry, Family Matters, 2002

The moving story of a troubled Mumbai family, set against the backdrop of the city.

"In the flower stall two men sat like musicians, weaving strands of marigold, garlands of jasmine and lily, and rose, their fingers picking, plucking, knotting, playing a floral melody. Kariman imagined the progress of the works they performed: to supplicate deities in temples, honour the photo-frames of someone's ancestors, adorn the hair of wives and mothers and daughters.

The bhel puri stall was a sculptured landscape, with its golden pyramid of sev, the little snow mountains of mumra, hillocks of puris, and, in among their valleys, in aluminium containers, pools of green and brown and red chutneys …

It was all as magical as a circus, felt Kariman, and reassuring, like a magic show."

• Marine Lines

• Marine Lines

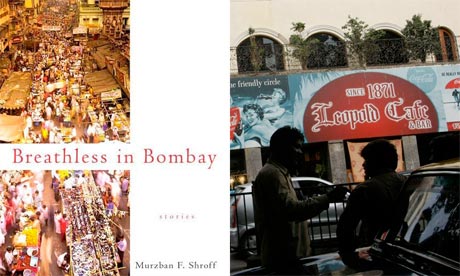

Murzban F Shroff, Breathless in Bombay, 2009

Fourteen brilliant stories set in contemporary Mumbai – shortlisted for the 2009 Commonwealth Writers' Prize.

"To walk along the streets of Colaba and to be wooed by peddlers of all trades, all motives, always involves me with a measure of excitement … To sit in Café Leopold and watch the world go by; and to sit on the parapet at Apollo Bunder and see the sail boats tossed on the coruscating waters; to walk past Jehangir Art Gallery and see the drug addicts huddled over their foil … to walk along the Gothic colonnades of the Ballard Estate and relive the solidarity of a lost era of architecture; to walk along Marine Drive and see the couples, their backs to the city, their heads huddled, a universal sun casting its light on them."

• Marine Drive

• Marine Drive

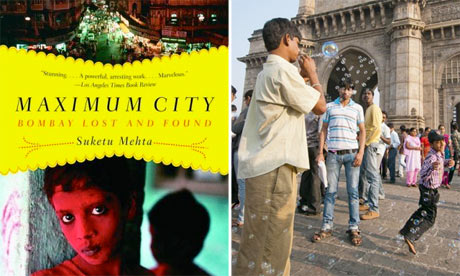

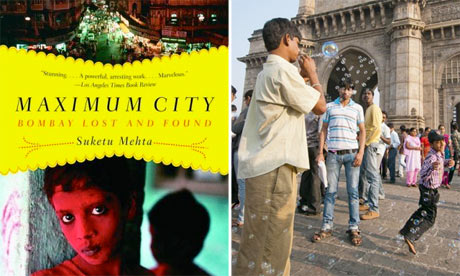

Suketu Mehta, Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found, 2004

Photograph: Public domain/David Pearson/Rex Features

Photograph: Public domain/David Pearson/Rex FeaturesThe definitive story of modern Mumbai in all its diversity and complexity.

"The Gateway of India, a domed arch of yellow basalt surrounded by four turrets, was built in Bombay in 1927 to commemorate the arrival, sixteen years earlier, of the British king, George V; instead, it marked his permanent exit. In 1947, the British left their Empire under this same arch, the last of their troops marching mournfully to the last of their ships … Cities are gateways; to money, to position, to dreams and devils. A migrant from Bihar might one day get to America; but first he needs a spell in the boot camp of the west: Bombay, the acclimatisation station."

• The Gateway of India

• The Gateway of India

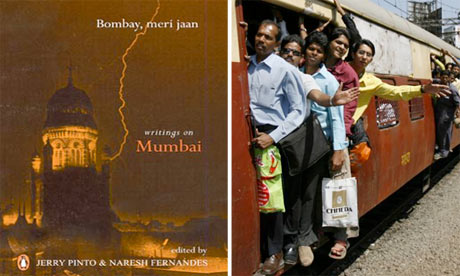

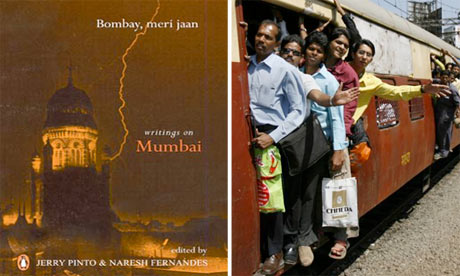

Jerry Pinto and Naresh Fernandes (eds.), Bombay, meri jaan, 2003

A wonderfully eclectic collection of essays on all things Mumbai.

"Asad, of all people, has seen humanity at its worst. I asked him if he felt pessimistic about the human race. 'Not at all,' he replied. 'Look at all the hands from the trains.'

If you are late for work in Bombay, and reach the station just as the train is leaving the platform, you can run up to the packed compartments and you will find many hands stretching out to grab you on board, unfolding outward from the train like petals. As you run alongside you will be picked up, and some tiny space will be made for your feet on the edge of the open doorway. The rest is up to you ...

And at the moment of contact, they do not know if the hand that is reaching theirs belongs to a Hindu or Muslim or Christian or Brahmin or untouchable, or whether you were born in the city or arrived only this morning, or whether you live in Malabar Hill or Jogeshwari; whether you are from Bombay or Mumbai or New York. All they know is that you're trying to get to the city of gold, and that's enough. Come on board, they say. We'll adjust."

• Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus

• Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus

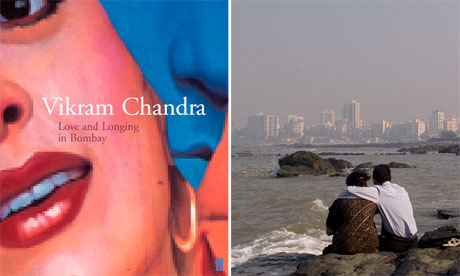

Vikram Chandra, Love and Longing in Bombay, 1997

Photograph: Public domain/Abraham Nowitz

Photograph: Public domain/Abraham NowitzFive haunting tales set in modern Mumbai and India.

"Ramani has been to Bandra that day; and he was telling them about a bungalow on the seafront. It was one of those old three-storied houses with balconies that ran all the way around, set in the middle of towering apartment buildings, and it had been empty as far back as anyone could remember …

'They say it's unsellable,' said Ramani. 'They say a Gujarati seth bought it and died within the month. Nobody'll buy it. Bad place.'

'What nonsense,' I said. 'These are all family property disputes. The cases drag on for years and years in courts, and the houses lie vacant because no one will let anyone else live in them.'

I spoke at length about superstition and ignorance and the state of our benighted nation, in which educated men and women believed in banshees and ghosts. 'Even in the information age we will never be free,' I said."

• Bandra

• Bandra

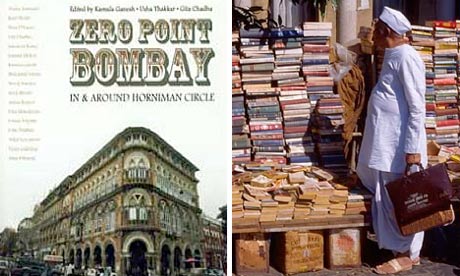

Kamala Ganesh, Usha Thakkar, Gita Chadha, Zero Point Bombay: In and Around Horniman Circle, 2008

Horniman Circle is both the birthplace of the city and still a centre of business life – both celebrated in 21 fascinating essays.

"From the iconic Strand Book Stall to the newly refurbished The Bookpoint, Horniman Circle must boast the biggest number of book stores anywhere in the country. The idea of opening a book shop came to TN Shanbhag, the owner of the Strand Book Stall, during a screening at the Strand Cinema. Having been humiliated in a reputed book store of the time for touching a book, the young Shanbhag wanted to start a book store where the access to Saraswati – the goddess of knowledge, music, arts and science – would not be restricted to the elite, but would be open to a wider section of the people. Shanbhag approached Keki Mody, the owner of the Strand Cinema, with his idea, and that is how the Strand Book Stall came into being on the premises of the cinema hall."

• Horniman Circle

• Horniman Circle

Kiran Nagarkar, Ravan & Eddie, 1994

From one of India's most popular novelists, a hugely entertaining novel that opens up the world of the city's sprawling chawls, or tenement blocks.

"Life in the chawls is a perpetual melodrama in itself. Large, mostly unhappy middle-class families packed in one building – not by choice, of course. Hence, there's a lot of scope for fights and quarrels over the slightest of things. Water is not a matter of quarrels but fully-fledged war. It turns housewives into warriors and water containers into missiles and cannons. Like in a small village, everyone knows everything about everyone else ... the prime mover is water. You snapped out of anaesthesia, interrupted coitus, stopped your prayers, postponed your son's engagement, developed incontinence, took casual leave to go down and stand at the common tap … cancelled going to church because water, present and absent, is more powerful than the Almighty."

• Mazagaon

• Mazagaon

Salman Rushdie, Midnight's Children, 1981

The epic story of Indian identity is also a glorious celebration of Mumbai itself.

"The Pioneer Cafe was not much when compared to the Gaylords and Kwalitys of the city's more glamorous parts; a real rutputty joint, with painted boards proclaiming LOVELY LASSI and FUNTABULOUS FALOODA and BHEL-PURI BOMBAY FASHION, with film playback music blaring out from a cheap radio by the cash-till, a long, narrow, greeny room lit by flickering neon, a forbidding world in which broken-toothed men sat at reccine-covered tables with crumpled cards and expressionless eyes."

• Churchgate

• Churchgate

• Malcolm Burgess is the publisher of Oxygen Books' city-pick series, featuring some of the best-ever writing on favourite world cities

Thursday, March 1, 2012

Tête-à-Tête With Thrity Umrigar

Thrity Umrigar is the best-selling author of the novels Bombay Time, The Space Between Us, If Today Be Sweet, The Weight of Heaven, and most recently The World We Found. She is also the author of the memoir, First Darling of the Morning.

Thrity was born in Bombay, India and came to the U.S. when she was 21. As a Parsi child attending a Catholic school in a predominantly Hindu country, sh had the kind of schizophrenic and cosmopolitan childhood that has served her well in her life as a writer. Accused by teachers and parents alike of being a daydreaming, absent-minded child, she grew up lost in the fictional worlds created by Steinbeck, Hemingway, Woolf and Faulkner. She would emerge long enough from these books to create her own fictional and poetic worlds. Encouraged by her practical-minded parents to get an undergraduate degree in business, Thrity survived business school by creating a drama club and writing, directing and acting in plays. Her first short stories, essays and poems were published in national magazines and newspapers in India at age fifteen.

After earning a M.A. in journalism Thrity worked for several years working as an award-winning reporter, columnist and magazine writer in America. She also earned a Ph.D. in English. In 1999, Thrity won a one-year Nieman Fellowship to Harvard, which is given to mid-career journalists.

While at Harvard, Thrity wrote Bombay Time. The publication and success of the novel allowed her to make a career change and in 2002 she accepted a teaching position at Case Western Reserve University, where she teaches creative writing, journalism and literature. She also does occasional freelance pieces for national publications and has written for the Washington Post's and the Boston Globe's book pages.

The Space Between Us was a finalist for the PEN/Beyond Margins award, while her memoir was a finalist for the Society of Midland Authors award. Thrity was recently awarded the Cleveland Arts Prize for midcareer artists. Her latest book The World We Found has gotten some great reviews and is also an Oprah magazine Pick, a Boston Globe Pick of the Week and a BookSense Pick. The Boston Globe calls it "a powerful meditation on friendship, on loss, and all the regrets of middle age, mingled with the recognition that for most of us it's not too late to remake our lives in some way."

You were a successful journalist, what prompted you to branch out to fiction?

I had always written poetry and fiction, years before I became a journalist. In fact, the only reason I became a reporter was that I couldn't conceive of a way to make ends meet by being a creative writer. Even as a journalist, I was drawn to "literary journalism," that is, telling longer, in-depth, human interest stories that tackled complex issues. But after years of doing this, I began to yearn to tell my own stories in my own voice and words. Thus, I decided to tackle my first novel, Bombay Time.

Where did the Nieman Fellowship fit into the timeline? Were you already writing fiction when you accepted it?

Where did the Nieman Fellowship fit into the timeline? Were you already writing fiction when you accepted it?In the mid-1990s, I was working full time, working on a Ph.D. in English part time, and trying to write my first novel somewhere in the midst of this. It soon became apparent that I had to set the novel aside if I was to finish my dissertation. But once I received my Ph.D., I was restless to tackle the novel again. So I applied for the Nieman Fellowship to Harvard, hoping that this would give me some free time. I received the Nieman in 1999 and immediately started working on the novel. I would wake up early in the morning, write for several hours and then start my day as a Nieman fellow. By the time the ten-month fellowship ended, I had written the novel and received a publishing contract.

Can you describe your transition from Journalism to fiction writing? What were the challenges you faced moving from factual to creative writing?

To be perfectly honest, switching to fiction writing was a joy. It was utterly liberating. To be able to write in my own voice, using my own words and thoughts and beliefs, was fantastic. Also, I think fiction enables a writer to come closer to describing the truth. Journalism, by definition, constraints you by forcing the journalist to stick to known facts. This can sometimes result in reductive, simplistic stories. But fiction lets you explore unknown worlds—people’s psyches, their inner thoughts, their dualities, their contradictions. I just find it richer grounds to explore.

Who and what do you read for pleasure?

Oh, gosh. The list is so long. I love Ian McEwan, Toni Morrison, Virginia Woolf, Luis Alberto Urrea, Jonathan Safran Foer, Kiran Desai.

If we examined your stack of "to read" books what would we find?

Queen of America by Luis Alberto Urrea

Behind the Beautiful Forevers by Katherine Boo

My Name is Red by Orhan Pamuk

What is the What by Dave Eggers

Who are some South Asian authors who inspire you and why?

I love Rushdie, Kiran Desai, Jhumpa Lahiri, Amitav Ghosh. They all have different writing styles and preoccupations and ambitions. But I love them all because they all write beautifully and they are serious in their ambitions—that is, their writing is meaningful because it stands for something, it represents something.

What do you think are some challenges faced by South Asian writers?

|

| Thrity at one of her many readings |

Frankly, this is a great time to be a South Asian writer because there are so many opportunities and we’ve been represented by such great writers who have earned their place in the literary pantheon. But the greatest challenge is that even today, many publishing houses feel satisfied if they have one or two South Asian writers. There is still an informal “quota” system and it’s difficult for new writers to crack that.

Describe the room/space where you do most of your writing.

My study. It’s a good-sized room with two desks. My computer overlooks my back yard and I look out onto squirrels chasing each other and birds drinking from the bird water pond. And of course, I see the sky. I don’t think I could write without looking at the sky. Sometimes, I hear my neighbor whistling to himself as he gets into this car.

What are some devices / prompts that you use to overcome writers block?

I refuse to believe in writers block. I refuse to talk about writers block. <smiles>

So, what's next for you?

I’m working on another novel. It’s titled I Begins. It tells the story of the friendship between two women—an immigrant woman whose husband owns an ethnic grocery store and her African-American therapist. It’s an examination of how the power balance in friendships alters over time.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)